We – at the SCF Community – are not immune to the standard and regulation… frenzy. Following our work from last year, we are completing our research of 1000 public corporates, for which we (reasonably) know whether they have a programme, and whether they disclose said programme.

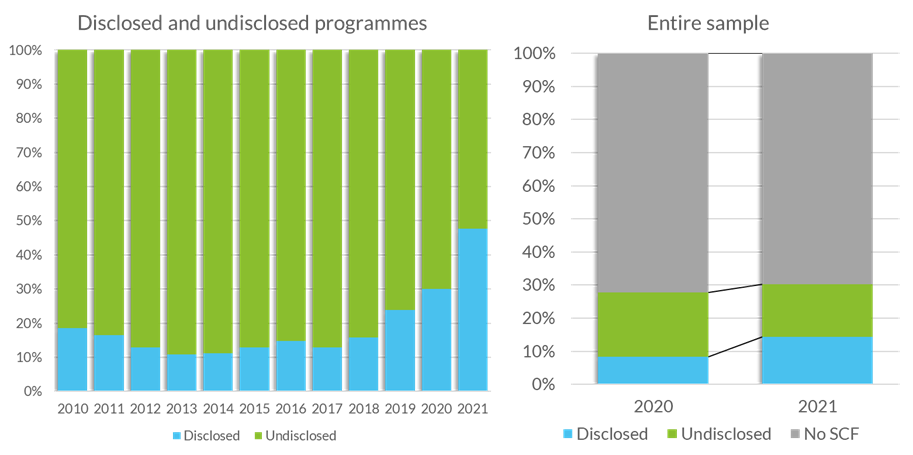

Results (based on 2021 annual reports) show that disclosure has increased substantially. We now estimate that – among public companies at least – there is a rough 50-50 split between companies that disclose their approved payable programme and those that don’t. The number of undisclosed programmes in our sample has actually shrunk by around 25% between 2020 and 2021.

Fig 1. Disclosure rates across our sample of around 1000 corporates, left: disclosed vs. undisclosed programmes, right: disclosed, undisclosed and no programme.

It’s tempting to go into the business of making predictions about what is going to happen with this change in regulations. More disclosure is often a source of heated debate. Is the SCF market going to be more transparent and less opaque? Or is this going to reduce volumes and hurt suppliers? Or maybe nothing will change.

We tend to have a neutral stance on this. Transparency is surely needed and good, but doubts remain on whether a paragraph in the annual report might be enough to provide ‘true’ transparency in the SCF market (would something have changed in the Greensill saga if those standards were in place then? Probably not).

However, instead of entering the rabbit hole of declaring impending changes as good or bad, let us offer two different perspectives on what they might entail.

Disclosure is not governance, but it is an opportunity. As we said last year, there is always a sort of overlap between disclosure and governance. While disclosure could very well be a tool for governance in the SCF market, it is not its substitute. Governance should not only aim at transparency, but also at fostering shared rules of the game, allowing flexibility and innovation and actively working towards avoiding crises. To what extent (strictly) enforced standards work in this direction might be up for debate. Disclosure for the sake of disclosure would hardly hit the governance target. However, it is up to the SCF industry broadly speaking to take the lead towards more governance in SCF. To what extent this will happen, remains to be seen.

That said, good or bad, there’s no doubt that an increase in disclosure is an opportunity. For example, it seems likely that a part of the current trend towards ESG-linked programmes might be boosted by the impending necessity of disclosing the current SCF programme. For as much as ESG-linked programmes might have some criticalities (beware the ‘g’-word!), they are a nice twist on the traditional approved-payable financing programme. Such a trend would surely be welcomed.

The SCF echo-chamber. However, there is indeed a concrete risk from an excessive focus on disclosure and reclassification risk. It is that it narrows the discourse around SCF even further within the space of an already mature view of what SCF is. We have said many times that our position is that SCF should aim at going beyond approved payable financing. We see in that a win-win-win (just to stay within SCF language) for both corporates and suppliers, as well as SCF providers.

However, there is undoubtedly a self-enforcing narrative around SCF, an inertia that pushes it back towards the type of programme that made the name famous. This is problematic, as it impedes innovation. In this line of thinking, strong and strict regulations might standardize the SCF market even further – and for what benefits it might bring, this will surely cost.

Through the grapevine, we have heard already about projects and innovations put on hold, paused, if not stopped. Standards might contribute to reinforcing the SCF echo-chamber, meaning the idea that SCF can and should always equate to approved payable financing programmes and that deviating from that is in itself the cause of crises such as Greensill., The idea that avoiding such deviations might avoid further crises.

This – to us here at the SCF Community – doesn’t seem like a productive route for the SCF industry. And as much as we support transparency in the market, we also like to have a dynamic SCF market that looks at the future rather than being stuck in the present.

We discuss these topics, as well as the entire research, on March 27th at 4PM CET, following which our white paper detailing the full results of the research will be available. You can register for the webinar and receive the white paper right after it at this link. Looking forward to seeing you there!